Latino leaders could collaborate with Black communities. Why don’t they?

The two groups have different views on whether racism is systemic or not, our research finds. It wasn’t always this way.

Analysis by Claudia Sandoval and Chaya Crowder

October 14, 2022 at 7:00 a.m. EDT

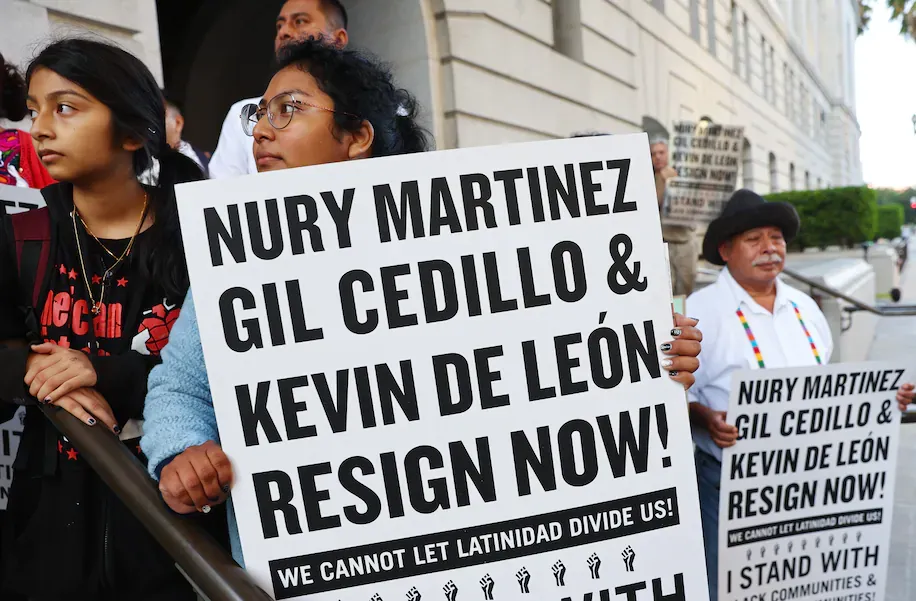

This week, a recording of Latino Los Angeles City Council members making racist comments burst into the news. But Latino anti-Black racism is not new or surprising. A number of scholars have examined the conflict between these two groups, including Efren Perez and colleagues, here at The Monkey Cage.

Blacks and Latinos are more likely to move into neighborhoods dominated by the other group than into predominantly White neighborhoods, which means they are especially likely to have social and political interactions. But our research finds that the Black-Latino relationship is complicated by the fact that these two communities think of racial solidarity in fundamentally different ways. Here’s what that means for collaboration.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Black and Brown communities worked together in Los Angeles politics.

The Black and Latino communities appeared to join in political solidarity during the 1960s and ’70s, with a wave of civil rights protests across the United States. In Los Angeles, the Chicano movement borrowed tactics heavily from the Black Panther party. A group that called itself the Brown Berets sponsored walkouts in East Los Angeles to protest police brutality, advocate for better housing and education, and protest the U.S. war in Vietnam.

As with so much activism from that period, this died down by the 1990s. Latino populations in places such as Los Angeles grew larger than the Black population, leading scholars and other observers to begin discussing conflict and competition between the groups.

Many scholars and political observers have assumed these groups are competing over a limited set of resources — with one group or the other getting more or less of, say, job opportunities and political power. For instance, as apparently was happening in the offensive Los Angeles conversation, discussions of redistricting often turn into debates over whether one community or the other will have more or less influence over choosing the potential representative from a particular district.

But it doesn’t have to be that way. The two groups could instead work to build solidarity so as to gain power for both. However, achieving that requires that groups consider how their marginalization is similar, different and at times connected to the oppression of others. We found that Latino folks are less likely to perceive systemic oppression in general.

How Black and Latino people did in this last round of redistricting

How we did our research

To examine whether these communities think about solidarity in the same way, we analyzed data from the 2020 Collaborative Multiracial Post-Election Survey — which contains large, randomly selected national samples of both Black and Latino respondents, totaling 4,071 and 3,529 respectively — to better understand the dynamics between these two groups. This online survey was administered between April 2, 2021, and Aug. 25, 2021. The survey was available to respondents in English, Spanish, Chinese, Korean, Vietnamese, Arabic, Urdu, Farsi and Haitian Creole. The full data are weighted within each racial group for age, gender, education, nativity and ancestry.

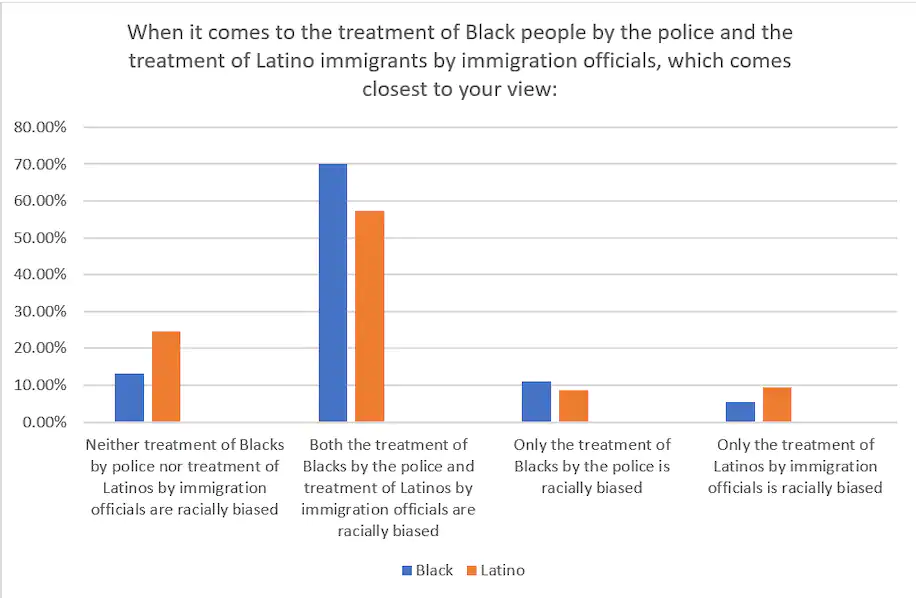

One survey question asked: “When it comes to the treatment of Black people by the police and the treatment of Latino immigrants by immigration officials, which comes closest to your view?”

Why are prominent Los Angeles Latinos saying such racist things?

Blacks are more likely than Latinos to see racism as systemic

We find that Black respondents are significantly more likely to say both Black and Latino communities experience racially biased discrimination. In fact, Latino respondents are 10 percentage points more likely than Black respondents to say neither the treatment of Blacks by the police nor the treatment of Latino by immigration officials is racially biased.

Many of our Latino respondents do not believe in the existence of systemic racism in the United States. Some believe their individual efforts will be rewarded, regardless of race, while others compare their new experience to the turmoil back home.

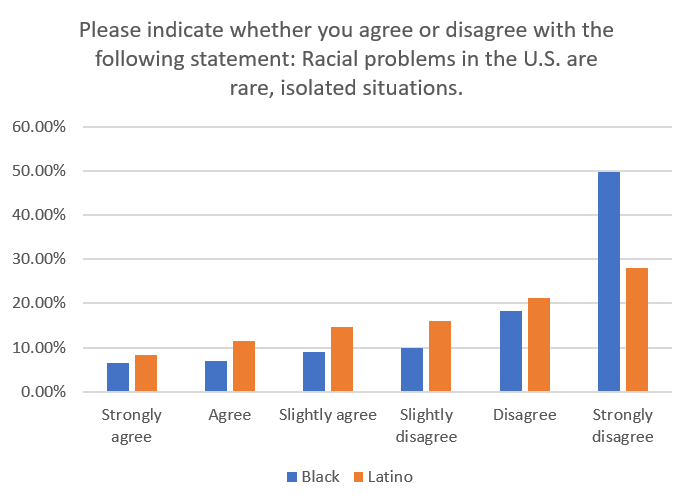

We also asked whether respondents agreed or disagreed with the statement “Racial problems in the U.S. are rare, isolated situations.” We found a more than 10 percentage point gap between the two groups: 77 percent of Black respondents disagreed, but only 65 percent of Latinos. In other words, more Black Americans see racism as systemic.

Further, we found that belief in systemic racism in the United States is the strongest predictor of solidarity between these two communities. Our research demonstrates that Latino people who disagree with the idea that racial problems are rare, isolate situations are more likely to believe the treatment of both Black and Latino people is racially biased.

Of course, some groups may nevertheless prefer to strategize about how to obtain more political power for their own communities than to work on building coalitions among communities. However, the racist discussion among L.A. council members and allies was not about building resources; rather, it expressed gratuitous racism. The remarks suggest what we found in our data: Without a sense of a shared fate in facing systemic issues, communities are likely to compete rather than collaborate.

Chaya Crowder (@ChayaCrowder) is an assistant professor in the department of political science and international relations at Loyola Marymount University, where her research focuses on the intersection of race, gender and American political behavior.

Claudia Sandoval is an assistant professor in the department of political science and international relations at Loyola Marymount University, where her research focuses on Black/Latino relations, immigration, and Latino politics.